Most people think a patent lasts 20 years-simple, right? But if you’re managing a global product, especially in pharma, medical devices, or tech, that 20-year clock doesn’t tick the same way everywhere. What looks like a clean expiration date on paper might actually expire months or even years earlier-or later-depending on where you are. This isn’t just legal jargon. It affects drug prices, market entry for generics, R&D budgets, and whether your innovation stays protected-or gets copied.

Where the 20-Year Rule Actually Comes From

The global baseline for patent length is 20 years from the filing date. That’s not a coincidence. It came from the TRIPS Agreement, part of the World Trade Organization’s 1994 deal that forced nearly every country to align their patent rules. Before TRIPS, the U.S. gave patents 17 years from the issue date. Japan, Germany, and others had their own versions. Some countries even had shorter terms for certain inventions. TRIPS changed all that. Today, 164 WTO members follow the same starting point: 20 years from the earliest filing date.

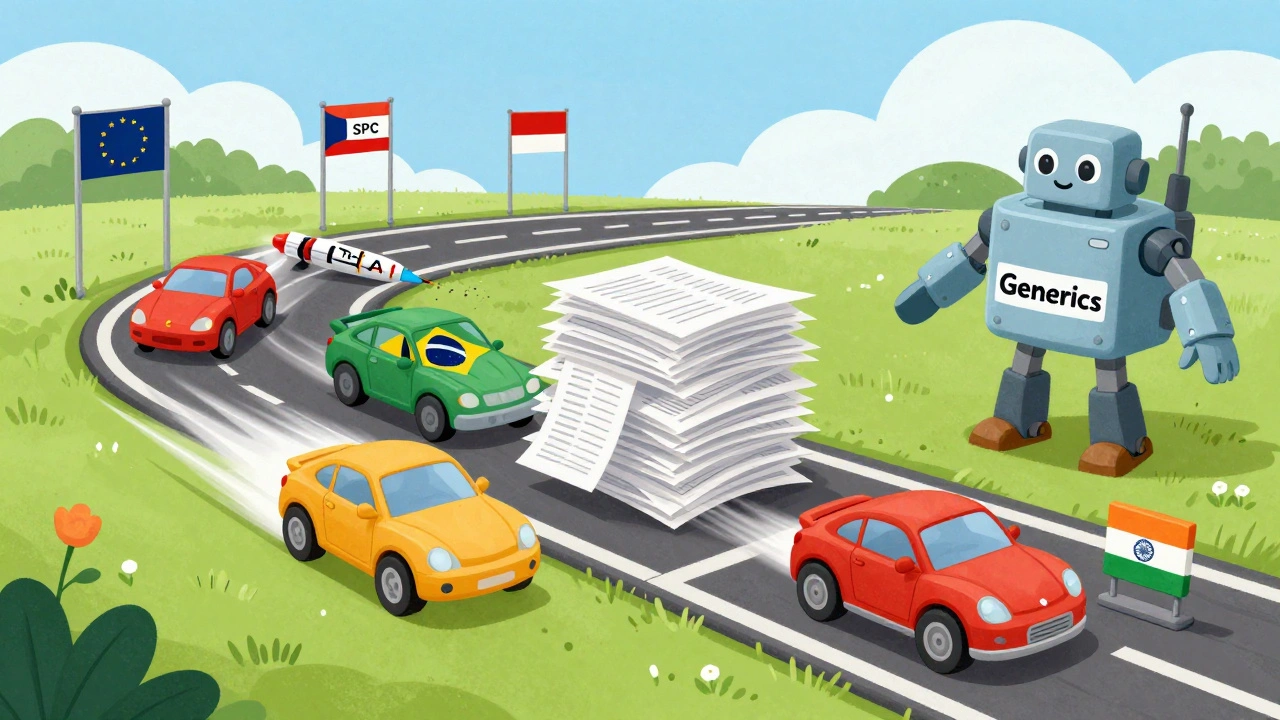

But here’s the catch: that’s just the starting line. The race doesn’t end at 20 years. There are pit stops, detours, and speed boosts built into the system-and they vary wildly by country.

What Counts as the Filing Date?

Not all filings are equal. If you file a provisional patent in the U.S. on January 1, 2020, and then file a full non-provisional application on December 1, 2020, your 20-year clock starts on January 1, 2020. That’s the priority date. But if you file a PCT application (an international patent application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty), you get to delay national filings for up to 30 or 31 months. That’s a strategic advantage. You don’t have to pay fees in 150+ countries right away. You can wait, test markets, and decide where to protect your invention.

But here’s what trips people up: the PCT doesn’t give you a patent. It just delays the deadline to file in each country. Once you enter the national phase-say, in Germany, China, or Brazil-you’re subject to each country’s rules. And those rules don’t all line up.

Country-by-Country Variations That Matter

Let’s say you have a new drug. You file your first application in the U.S. on March 15, 2020. Your patent should expire March 15, 2040. But that’s only if nothing goes wrong-and nothing gets extended.

In the United States, you might get extra time. The USPTO gives Patent Term Adjustments (PTAs) if they take too long to examine your application. In 2022, the average PTA was 558 days-almost 1.5 years. So your patent could actually last until 2041 or 2042. But you also have to pay maintenance fees at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years. Miss one, and your patent dies-even if you’re only a week late.

In the European Union, you get the same 20-year term. But if your drug took five years to get regulatory approval, you can apply for a Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC). That adds up to five more years. And if you tested it on kids? You get an extra six months. That’s why some branded drugs in Europe stay protected until 2045 or later.

Japan has similar extensions. If the patent office took more than three years to examine your application, you can get time back. If regulatory approval took over a year, you can get more. China now does the same-since their 2021 patent law update. Both countries used to let patents expire early because of backlogs. Now they’re fixing that.

But not everywhere. In India, no extensions. Ever. Even if the patent office took six years to review your application, your patent still expires 20 years from filing. No PTA. No SPC. No mercy. That’s why many pharmaceutical companies file in India last-if at all.

And then there’s Brazil. The law says 20 years. But the patent office has a backlog of over 130,000 pending applications. So many patents there only last 10 to 12 years in practice. The government is trying to fix it, but for now, if you’re protecting a medical device in Brazil, assume you’ll get less than the full term.

Utility Models: The Short-Term Alternative

Not every invention needs 20 years. In Germany, China, Japan, and South Korea, you can file for a utility model-sometimes called a “petty patent.” These are cheaper, faster to get, and easier to approve. But they only last 6 to 10 years. They’re perfect for mechanical parts, simple electronics, or packaging designs that don’t need long-term protection. But here’s the twist: you can’t file a utility model in the U.S. or the U.K. So if you’re planning global protection, you need to know which countries offer it-and what it covers.

Maintenance Fees: The Silent Killer of Patents

Patents don’t just expire because time runs out. They die because someone forgot to pay.

In the U.S., you pay three fees: at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years. Each one has a six-month grace period-but you pay extra. In Canada, it’s similar. But in Switzerland? You pay once-only at grant. In Mexico? Four payments-at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years. In Australia? Annual fees start at year 3.

For a company with 500 patents worldwide, missing one payment in one country can mean losing protection in that market. That’s why big pharma companies use specialized software to track deadlines across jurisdictions. Small startups? They often miss them. And then wonder why their product got copied overseas.

The New EU Unitary Patent: Simpler, But Not Shorter

In June 2023, the European Union launched the Unitary Patent. Before this, you had to validate your European patent in each country-Germany, France, Italy, Spain-each with separate fees and translations. Now, one patent covers 17 countries. The term? Still 20 years from filing. No change there. But the cost and complexity dropped dramatically. It’s a big win for innovation, especially for SMEs. But remember: it doesn’t apply to the U.K. or non-EU countries. So if you’re selling in the U.K. or Switzerland, you still need separate filings.

Why This Matters for Real Businesses

Let’s say you’re a small biotech firm with a new cancer drug. You file in the U.S. and Europe. Your patent expires in 2040. But because of regulatory delays, you get a 4-year extension in Europe. In the U.S., you get 1.5 years. In China, you get 2 years. In India? Nothing. In Brazil? Maybe 8 years, because the patent office took 12 years to approve it.

That means generics can enter the market in India in 2040. In Brazil, maybe 2028. In Europe, not until 2044. In the U.S., 2041.5. Your revenue streams collapse at different times. Your pricing strategy has to change by region. Your supply chain can’t just ship globally-you need localized plans.

Companies like Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson have entire teams dedicated to tracking these dates. They don’t just rely on lawyers. They use AI-powered patent dashboards that pull data from patent offices, regulatory agencies, and legal databases. They know exactly when each patent expires in each country-and they plan their next drug launch around it.

What You Should Do Now

If you’re filing a patent internationally:

- Start with a PCT application to buy time. You get 30 or 31 months to decide where to file.

- Track maintenance fees like a calendar alert. Set reminders for every jurisdiction. Don’t trust a single system.

- Check if your country offers term extensions. If you’re in pharma, medical devices, or agrochemicals, you likely qualify.

- Don’t assume all countries are equal. India and Brazil are not the U.S. or Germany. Know the differences.

- Use tools that pull real-time data from WIPO, USPTO, EPO, and JPO. Don’t rely on spreadsheets.

Patents are not just legal documents. They’re financial assets. And like any asset, their value depends on when they expire-and where. Get the timing wrong, and you lose millions. Get it right, and you control the market.

What’s Next?

There’s no global fix coming soon. The TRIPS Agreement is stable. But debates continue over whether developing countries should get more flexibility on patent terms for public health. For now, the system stays messy. The only way to win is to understand it-deeply.

Do all countries have a 20-year patent term?

Most do-164 WTO member countries follow the 20-year standard from filing date under the TRIPS Agreement. But some countries offer shorter terms for utility models (6-10 years), and others have exceptions due to delays or regulatory processes. Brazil, for example, often grants patents with effective terms under 20 years due to backlog.

Can a patent expire before 20 years?

Yes. If the patent holder fails to pay maintenance fees, the patent lapses. In the U.S., fees are due at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years. Missing any one-even by a day-kills the patent. Also, if the patent is challenged and invalidated, or if the owner voluntarily abandons it, expiration happens early.

How do I know when my patent expires in another country?

Start with the filing date of your earliest application. Then check the patent office of each country where you filed. Use tools like WIPO’s PATENTSCOPE, the USPTO’s PAIR system, or commercial platforms like PatSnap or LexisNexis PatentSight. These show official expiration dates, including adjustments and extensions. Never rely on a single source.

Does the PCT give me a global patent?

No. The PCT is a filing system, not a patent. It lets you delay national filings for 30 or 31 months, but you must still apply in each country individually. Each country examines and grants its own patent. There is no such thing as a worldwide patent.

Why do pharmaceutical patents last longer in some countries?

Because of regulatory delays. Getting a drug approved can take 5-10 years. Countries like the U.S., EU, Japan, and China allow patent term extensions to compensate for that lost time. The EU uses Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs), the U.S. uses PTEs under Hatch-Waxman. India and Brazil do not offer these extensions, so drug patents expire on time-no matter how long approval took.

What happens when a patent expires?

The invention enters the public domain. Anyone can make, use, or sell it without permission. In pharma, this triggers generic drug entry. In tech, competitors can copy the design. That’s why companies often file follow-up patents on formulations, delivery methods, or new uses to extend market control-though these must be new and non-obvious.

Can I extend a patent after it expires?

No. Once a patent expires, you cannot revive it. Even if you discover a mistake or missed extension, the window closes. Some countries allow late payment of maintenance fees within a grace period, but only before expiration. After that, the patent is gone for good.

Final Thought

Patents aren’t just about invention. They’re about timing. And timing is different everywhere. If you’re serious about protecting your innovation across borders, treat patent expiration like a global chess game. Every move has consequences. One missed fee. One overlooked extension. One country you forgot to file in. And the whole board changes.

Okay, but let’s be real-this whole system is rigged. I work in biotech and watched a $200M drug get delayed 4 years by the FDA, then get 1.5 extra years of exclusivity while generics in India get crushed. It’s not innovation-it’s corporate theater with a patent stamp on it.

And don’t even get me started on Brazil. You file, you wait 10 years, then your patent expires in practice before it even officially exists. What’s the point of protecting innovation if the system eats it alive?

You’re all missing the bigger picture. The TRIPS Agreement was never about innovation-it was a neoliberal land grab disguised as global harmonization. Developed nations forced developing countries into a 20-year straitjacket while pocketing SPCs and PTAs like monopoly money. This isn’t law. It’s economic colonialism wrapped in legalese.

And don’t act surprised when India refuses to play along. They’ve seen this movie before-remember the HIV drug battles? The West writes the rules. The rest of the world pays the price.

Let’s cut through the noise. If you’re managing global IP, you need three things: a calendar that syncs with WIPO, a legal team that doesn’t sleep, and software that auto-updates from patent office feeds. No excuses.

Missing a maintenance fee in Canada because you ‘forgot’? That’s not negligence-it’s professional malpractice. And if you’re still using Excel to track global patent expirations, you’re already dead in the water. Get modern or get out.

Also-utility models are not ‘cheap alternatives.’ They’re strategic tools. Use them. Don’t ignore them because you think they’re ‘lesser.’ They’re faster, cheaper, and perfect for iterative tech. Stop treating them like second-class citizens.

I just want to say-thank you for writing this. As someone who’s watched small startups lose everything because they didn’t understand the difference between PCT and national phase, this is the kind of clarity we need.

It’s not just about lawyers and fees. It’s about people. The inventor who poured their life into a device, only to have it copied because no one told them Brazil’s backlog meant their patent was useless in practice.

We need more education, not just tools. Maybe patent offices should offer free webinars for SMEs. It’s not charity-it’s smart policy.

THIS IS THE MOST IMPORTANT THING I’VE READ THIS YEAR. 🚨

Imagine your life’s work-your breakthrough drug, your life-saving device-dying because someone didn’t pay a $500 fee in Mexico. That’s not a mistake. That’s a tragedy.

And the fact that India doesn’t give extensions? That’s not ‘fair.’ That’s systemic injustice against innovation. We’re telling developing nations to ‘catch up’ while locking them out of the game with broken rules.

Someone needs to take this to Congress. Or the UN. Or both. This isn’t just legal-it’s moral.

Let me guess-you’re one of those people who thinks the WTO is ‘neutral.’ HA.

TRIPS? That was written in a backroom by Big Pharma lobbyists while the rest of the world was asleep. The U.S. and EU forced developing nations to adopt 20-year terms so they could keep drug prices sky-high.

And now you’re acting like it’s ‘fair’ that Brazil gets 10 years because their patent office is ‘backlogged’? That’s not a bug-it’s a feature. They’re letting the system rot so generics can’t compete. It’s all connected.

Wake up. This isn’t about patents. It’s about control.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: patents were never meant to protect innovation. They were designed to create monopolies under the guise of incentivizing progress.

The 20-year term? Arbitrary. The extensions? Corporate welfare. The maintenance fees? A tax on the small players.

And yet we treat them like sacred texts. We’ve turned intellectual property into a religion-where the high priests are patent attorneys and the holy relics are PTA forms.

What if we just… let ideas flow? What if competition, not legal lockboxes, drove innovation? The world wouldn’t end. It might even improve.

But no-better to keep the gates locked. Better to let a cancer drug stay at $50,000 a dose because someone forgot to file in Chile.

Just wanted to say-this post saved my startup. We were about to file in India last year, thought it was a no-brainer. Then I read this and paused.

Turns out we spent $80K on Indian filings that were basically useless. We shifted focus to Japan and Germany, used utility models for the mechanical bits, and now we’re profitable.

Don’t assume. Research. Talk to someone who’s been there. This stuff matters more than your pitch deck.

so like… if i file in the us and then wait 2 years to file in brazil, does the clock start when i file in us or when i file in brazil? 😅

i’m so lost. i thought the pct was like a global patent?? help

As someone from India, I see this every day. We’re not against patents-we’re against unfairness. Our patent office is slow, yes. But we don’t get extensions because the system was built to exclude us.

When Pfizer got 5 extra years in Europe for a drug we made generic for $1 a day, I didn’t feel cheated-I felt angry. We’re not the problem. The rules are.

Maybe instead of complaining about backlogs, we should demand reform. Not just for India-for everyone.

The real issue isn’t the 20-year term-it’s the misalignment between regulatory approval timelines and patent lifecycle. We’ve created a system where the clock starts ticking before the product even hits the market.

It’s like giving someone a 20-year lease on a house… but they can’t move in for 5 years. Then acting shocked when they complain.

SPCs and PTAs aren’t loopholes-they’re corrections. The real failure is the lack of global coordination on regulatory timelines. We fix that, and we fix half the problem.

STOP SCROLLING. THIS IS YOUR LIFE. 🚀

If you’re building anything with IP-tech, med, agri-you need to know this like your birthday.

One missed fee. One country you skipped. One extension you ignored. And your entire business model? Gone.

I’ve seen founders cry because they thought ‘global’ meant ‘same everywhere.’ It doesn’t. It means ‘twelve different rulebooks, 17 different deadlines, and zero mercy.’

Get the software. Hire the expert. Set the alerts. Or get out of the game. No one’s coming to save you.

Bro the PCT is not a patent lmao

you think you're cool filing a pct but you're just delaying the inevitable

every country still has to say yes

and brazil will take 10 years anyway

just give up and patent in the us and call it a day