When you walk into a pharmacy in the U.S. and see a $6 copay for your generic blood pressure pill, it’s easy to think you’re getting a deal. But here’s the twist: generic drugs in the U.S. are often cheaper than in nearly every other developed country. Meanwhile, the brand-name versions of those same drugs? They cost nearly four times more than they do overseas. This isn’t a contradiction-it’s the reality of how American pharmaceutical pricing works.

Why U.S. Generic Drugs Are Cheaper

The U.S. doesn’t have a single government agency setting drug prices. Instead, it relies on market competition. When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, multiple generic manufacturers rush in. The FDA approved over 770 generic drugs in 2023 alone. Each new competitor drives prices down. By the time three or four generic makers are selling the same pill, the price often drops to just 15-20% of the original brand’s list price. That’s why your 30-day supply of metformin costs $4 at Walmart and $12 in Germany. According to a 2022 RAND Corporation study for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. generic drug prices were 33% lower than in 33 other OECD countries. France and Japan, which tightly control drug pricing, still pay more for generics than Americans do. Even Canada, often seen as a model for affordable care, spends more on generic medications per prescription. The reason? Scale and volume. Ninety percent of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generics. That’s far higher than the 41% average in other developed nations. Pharmacies and insurers use that massive volume to negotiate deeper discounts. When you buy 10 million pills a year, you can demand a price that smaller markets can’t match.Brand-Name Drugs: The Real Cost Driver

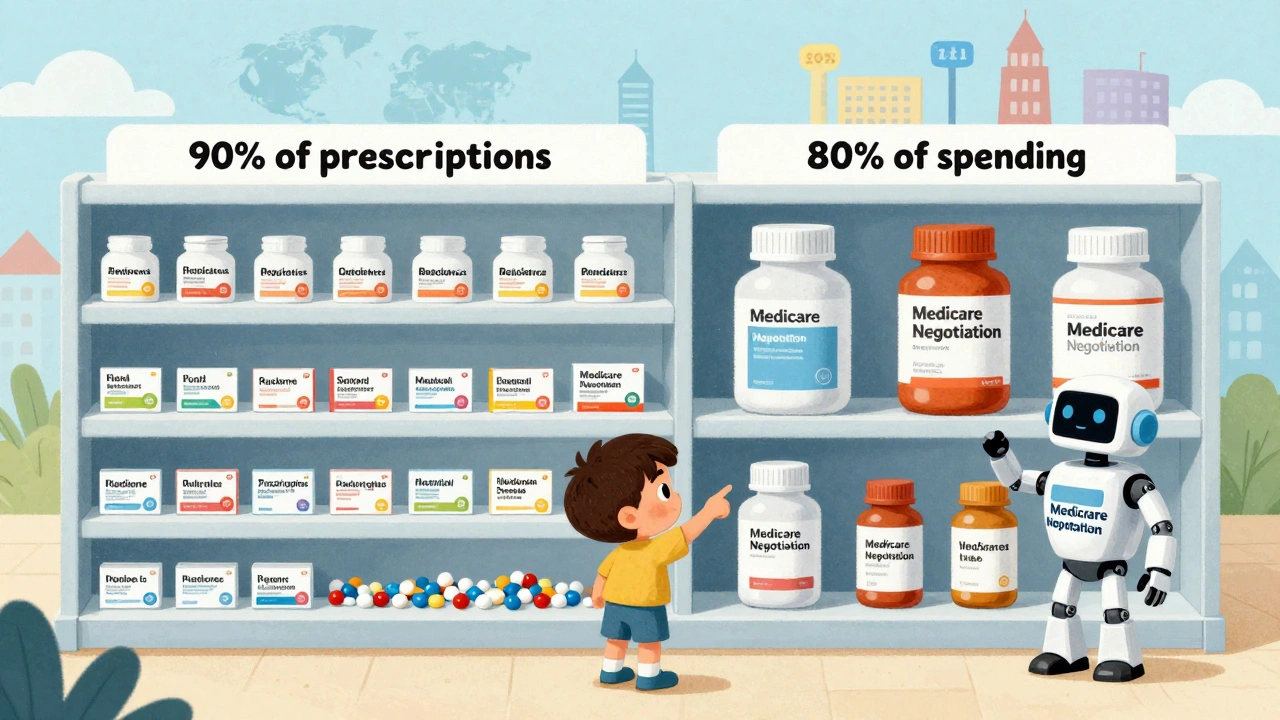

Here’s where things get expensive. While generics are cheap, brand-name drugs in the U.S. are the most costly in the world. The same RAND study found that U.S. prices for originator drugs-brand-name drugs with no generic competition-were 422% higher than in other countries. For example, the diabetes drug Jardiance costs $204 per month under Medicare’s negotiated price. In Japan, it’s $52. In Australia, it’s $48. This isn’t because American companies are greedy. It’s because the U.S. system doesn’t cap prices. Drugmakers set list prices based on what they think the market will bear. Without government negotiation (outside of Medicare’s limited program), they can charge whatever they want-until generics arrive. The result? Even though 90% of prescriptions are for generics, those 10% of brand-name drugs account for nearly 80% of total spending. A single cancer drug or autoimmune treatment can cost $10,000 a month. That’s why overall U.S. pharmaceutical spending is nearly triple the OECD average, even though most people aren’t paying those prices directly.Net vs. List Prices: The Hidden Math

You might hear that U.S. drug prices are the highest in the world-and technically, that’s true. But that’s based on list prices, the sticker price before discounts. The real price paid? That’s the net price, after rebates, discounts, and negotiations. A 2024 study from the University of Chicago found that when you look at net prices paid by public programs like Medicare and Medicaid, the U.S. actually pays 18% less than peer countries. Why? Because U.S. insurers and government programs aggressively negotiate rebates. A drugmaker might list a drug at $1,000, but if Medicare buys 500,000 doses, they might pay $600 after a 40% rebate. In countries with single-payer systems, the government sets the price upfront-no negotiation, no rebate. So the listed price is the final price. This is why international comparisons can be misleading. If you only look at list prices, the U.S. looks like a price gouger. But if you look at what actually changes hands, the story changes. For generics, the U.S. wins. For brand-name drugs, the U.S. still pays more-but not as much as the list price suggests.

How Other Countries Keep Prices Low

Most other developed countries use price controls. France, Japan, and Germany set maximum prices based on a drug’s perceived value, not what a company wants to charge. They also use “reference pricing”-if a drug costs $100 in Germany, France won’t let it cost more than $90. Japan’s system is especially effective. The government re-negotiates prices every two years. If a generic version enters the market, the price of the brand drops immediately. This forces companies to innovate or lose revenue fast. It’s why Japan has the lowest drug prices in the world-for both brand and generic drugs. The U.K. and Canada have similar systems. Their public health systems buy in bulk and set prices that reflect what the country can afford-not what a company thinks it’s worth. The trade-off? Longer wait times for new drugs. In the U.S., you get the latest treatments faster-but you pay more.Why the U.S. Still Pays More Overall

Even with cheaper generics, the U.S. spends more per person on drugs than any other country. Why? Because of what happens when a new, expensive drug hits the market. When a new brand-name drug comes out, there’s no price cap. Insurers and patients pay full list price until generics arrive-sometimes years later. The FDA’s 2023 report shows that the average generic copay is $6.16. The average brand-name copay? $56.12. That’s nearly nine times more. Medicare’s new negotiation program, which started in 2023, is trying to fix this. It’s negotiating prices for 10 high-cost drugs in 2024, with more coming each year. But even those negotiated prices are still higher than what other countries pay. For example, Medicare pays $4,490 for Stelara, a psoriasis drug. In Germany, the price is $2,822. In Australia, it’s $2,700. The gap isn’t closing fast. And while generics keep everyday meds affordable, the real financial burden falls on people who need specialty drugs-those with cancer, autoimmune diseases, or rare conditions.

Let’s cut the crap. The U.S. doesn’t have a drug pricing problem-it has a corporate capture problem. Pharma CEOs make more in a week than your entire family makes in a decade. They don’t care about innovation-they care about profit margins. And you? You’re the sucker paying for their yachts.

Generics are cheap because they’re commoditized. But when a new cancer drug drops? $100K a year. No negotiation. No limits. Just greed dressed up as ‘R&D.’

They call it ‘market freedom.’ I call it legalized robbery. And the worst part? You’re told to be grateful you’re not paying $200 for metformin. Meanwhile, your neighbor can’t afford insulin. That’s not a system. That’s a hostage situation.

Stop pretending this is about competition. It’s about power. And power doesn’t care if you live or die.

Fix this or burn it all down.

OH MY GOD. I just had a full-body epiphany. So let me get this straight: the U.S. is basically the global pharmaceutical R&D piggybank? We pay absurd list prices for brand-name drugs so the rest of the world can get them on sale? Like we’re the financial backbone of global health equity?

It’s insane. It’s poetic. It’s tragic. It’s the ultimate capitalist paradox-where the most expensive system is also the one funding the world’s medical breakthroughs.

And don’t even get me started on the net vs. list price sleight-of-hand. It’s like Amazon listing a PS5 at $1,000 but giving you a $700 rebate-except you never see the rebate. Medicare gets it. You? You get the sticker shock.

Meanwhile, Japan’s re-negotiating prices every two years like it’s Black Friday on a national scale. We’re still arguing over whether to let Medicare haggle. We’re literally behind the curve.

Someone needs to write a musical about this. ‘The Price of Life: A Tragedy in Four Acts.’ I’ll write the ballad. You bring the tissues.

I read this and just stared at my prescription bottle for ten minutes.

It’s not that I’m angry. It’s that I’m numb.

My antidepressants cost $12. My mom’s heart meds? $8. We’re lucky. We’re not the ones drowning.

But I think about the people who aren’t. The ones who skip doses. The ones who cry in parking lots. The ones who die because the math didn’t add up.

I don’t know what to do. I just… feel it. All of it.

And I’m tired.

Let’s be clear-this isn’t about ‘fairness.’ It’s about sovereignty. Other countries are leeching off American innovation while pretending they’re moral. They cap prices because they don’t want to pay for the R&D that happens here. We’re the ones taking the risk. We’re the ones funding the future.

And now you want to turn us into Canada? You think that’s progress? That’s surrender.

Generics are cheap because we have competition. That’s American capitalism at work. Don’t ruin it because you can’t handle the truth: the U.S. pays more so the world can get cheaper drugs.

Stop whining. Start producing.

My sister’s on a $14,000-a-month cancer drug. She’s on Medicare. They negotiated it down to $9,000. Still unaffordable.

I know people who pay $6 for metformin. I know people who cry over their pill bottles.

This isn’t a political issue. It’s a human one.

We can do better. We have to.

Let’s stop arguing about who’s right and start asking who’s suffering.

And then let’s fix it-together.

It’s worth noting that the RAND study’s methodology is robust, and the distinction between list and net pricing is critical to accurate international comparison. The U.S. system, while imperfect, generates innovation that benefits global health. The real challenge is extending affordability to the 10% who need specialty drugs without dismantling the engine that produces them.

Policy solutions must be nuanced: expand Medicare negotiation, incentivize generic entry, and explore value-based pricing. Eliminating profit incentives entirely risks stifling R&D. The goal isn’t to punish industry-it’s to align incentives with patient outcomes.

This is solvable. But it requires data-driven compromise, not ideological soundbites.

Hey, just wanted to say-this post made me feel seen. I’ve been on generics for years and honestly never thought about how they’re so cheap. It’s wild.

And I’ve got a friend on a $12K/month drug. She’s lucky to have insurance. I can’t imagine that weight.

Maybe we don’t need to pick sides. Maybe we just need to make sure no one gets left behind.

Small steps. Big impact. You’re not alone in this.

❤️

Oh wow. So the U.S. is the world’s drug lab and we get blamed for it? That’s rich. Other countries are happy to steal our innovation, then act like we’re the villains.

France? Germany? They don’t pay for R&D. They just say ‘no’ to prices. Easy. Convenient. Cowardly.

And now you want to copy them? You want to kill the golden goose? The same goose that gave you life-saving drugs last decade?

Wake up. This isn’t about fairness. It’s about free-riding. And we’re not playing along anymore.

Let’s be honest: this entire narrative is a distraction. The real story? The FDA, CMS, and Big Pharma operate as a single entity under the guise of ‘market freedom.’ The 770 generics approved in 2023? Most were manufactured by Chinese conglomerates with ties to state-owned enterprises. The ‘competition’ is a shell game.

And the net pricing ‘savings’? That’s just rebates funneled back to pharmacy benefit managers who pocket 20% before you ever see a pill.

This isn’t capitalism. It’s a cartel with a PowerPoint presentation.

And you? You’re the final node in the algorithm.